Judge Tarek Bitar. (Credit: DR)

An unprecedented war between the two judges has brought Lebanon’s judicial system, which has been long hit by economic hardships and political interference, to a virtual standstill.

Judge Tarek Bitar, the lead investigative judge on the probe into the 2020 Beirut port explosion, decided on Jan. 23 to restart the investigation, which had been suspended for more than 13 months because of unresolved dismissal requests against him.

Basing his decision on a legal study, upon resuming the probe Bitar immediately decided to release five of the 17 detainees implicated in it. He then initiated proceedings against politicians, civil servants and judges, including Ghassan Ouiedat, the country’s top prosecutor.

Oueidat had already stepped away from the case, citing kinship with Amal-affiliated MP Ghazi Zeaiter, who is also implicated in the probe.

The top prosecutor, however, now appears to be on the defensive, and in addition to ordering the security services not to comply with Bitar’s instructions, Oueidat also filed a complaint against him.

Things did not end here. On Wednesday, Oueidat went as far as to order the release of all 17 detainees arrested in the probe — a bombshell to many judges in office.

L’Orient-Le Jour asked several judges to gauge the repercussions of Bitar’s and Oueidat’s decisions for the judicial system.

While all agree that both judges made legal errors, Bitar’s mistakes are widely deemed “questionable,” but the judges interviewed for this article see Oueidat’s errors as “unforgivable.”

A ‘little too late’

“Bitar based his decision on a legal opinion that he built after a study,” says Camille*, 47-year-old judge. “While, from a legal point of view, one can take a position for or against his opinion, this does not mean that he has committed an ‘offense,’” he insists.

Camille explains that Bitar insists that an investigating judge at the Court of Justice cannot be dismissed — an opinion that comes a “little too late,” according to him.

“Bitar agreed to be appointed after the dismissal of his predecessor Fadi Sawwan in February 2021 by the Court of Cassation, which means he implicitly admitted that he could, in turn, be removed,” Camille explains.

Leila*, another judge, 43, refers to “extenuating circumstances,” namely that “Judge Bitar has been confronted for more than a year with obstacles that the competent authorities have not tried to overcome.”

In fact, the plenary session of the Court of Cassation, the court responsible for ruling on appeals against Bitar for “serious misconduct,” as well as other judges of the chamber of the Court of Cassation, responsible for considering appeals for dismissal also brought against the lead investigator, cannot convene for lack of quorum.

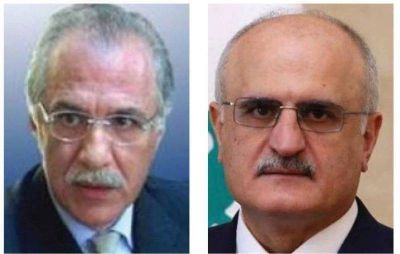

Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat. (Credit: DR)

Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat. (Credit: DR)

Caretaker Finance Minister Youssef Khalil, who close to Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, is blocking the draft decree of these partial judicial permutations that the Higher Judicial Council has referred to him.

For Lucien*, another 52-year-old judge, political interference does not justify the fact that Bitar has decided that he cannot be dismissed.

“Even if we understand that he wants to make a breakthrough in the investigation, Bitar should wait for the decision of the court before which the requests for recusal have been submitted,” Lucien says. “One can't be a judge of oneself.”

Clara*, 39, also a judge, speaks of the “contradictions” in Bitar’s approach.

She dwells in particular on the fact that when Bitar had taken the case in hand, he pronounced his incompetence to prosecute magistrates.

Bitar had then referred two summary judgment judges, Jad Maalouf, and Carla Chouah, to the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Cassation.

However, “in Bitar’s spectacular return last week, he decided to prosecute them,” she notes.

Grief and a black page

But Camille maintains that “while Bitar’s mistakes are tangible, those of the prosecutor are heavy and even constitute a huge offense.”

“The top prosecutor is not authorized to release prisoners,” he insists, adding that in this matter, “[Oueidat] cannot take up the role of a judge, but of a party that defends the victims, their relatives and society.”

Leila, meanwhile, adds, “Moreover, Oueidat had recused himself from the case, and this withdrawal had been ratified by a final decision of the Court of Cassation.” She stresses that “no legal reason can justify his re-emergence in the case.”

“I think, [Oueidat] felt danger approaching,” she says, adding that “sadly, personal interests prevail over the need for unanimity around the urgency to get to the bottom of what happened in the port case.”

Clara went on to say, “Oueidat does not seem to have studied the same laws as Bitar.”

“Although I have a law degree, then trained for four years at the Institute of Judicial Studies and practiced my profession as a judge for 12 years, I have never read laws that could justify his [Oueidat’s] steps," she adds.

In the same vein, Camille stresses the “gravity of the prosecutor’s interference and short-circuiting the decisions of judges in their own cases.”

“The solution lies in the adoption of a law on the independence of the judiciary that would put an end to the servile ingratiation that some judges feel they owe to the ruling class that appointed them,” Camille says.

Leila, who has replaced her profile picture on Instagram with a black photo, comments that “meanwhile, scattered to the four winds, the judicial system continues to collapse.”

“I am mourning justice,” she adds. “It has been stabbed in the heart.”

The current predicament of the justice system is difficult to describe.

“It is a farm,” one of the judges quoted above says. Another one of the interviewed judges deems the situation as “complete chaos.” Some of the judges, while speaking with L’Orient-Le Jour, say, “it’s an asylum,” or “madness.”

For Clara, the justice system has become a “jungle.” “I am sitting at my desk surrounded by files, in the middle of a jungle,” she insists.

“I keep wondering, what does it even matter if I continue to decide on my small cases, while one of the greatest crimes of humanity has not yet been solved,” Clara adds.

Camille, for his part, expresses his “disgust.” Lucien says the Justice Palace is no longer a place where he feels he belongs.

The same sentiment is echoed by Leila, who admits that she tried in vain to find another job. “I am staying because I have no choice,” she says.

* Names have been changed.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.