Volunteers clear a passage of debris and glass following the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — In the wake of the deadly blast two years ago at the Beirut port, the surrounding neighborhoods were covered in rubble and debris, the streets blanketed with shards of glass. But a glimmer of hope pierced through the devastation the next day, when thousands of volunteers appeared — seemingly out of nowhere — with brooms and shovels.

People of all walks of life began a clean-up process that in some cases would go on for months. Volunteers handed out sandwiches and bottled water and organized housing for those displaced. Later, they helped with the most urgent repairs needed in damaged homes and businesses, installing new doors and windows to replace those shattered by the blast.

With the state largely absent and international organizations slow to act, Lebanon’s civil society mobilized quickly and in force.

L’Orient Today caught up with some of the volunteers who took to the streets in the days and weeks after the explosion to see where they are today and to recount their journey on the ground.

Since the explosion, some have emigrated and others have stayed. For some, the days, weeks or months they spent volunteering were a brief interval; for others, they segued into a career in humanitarian work.

Here are some of their stories.

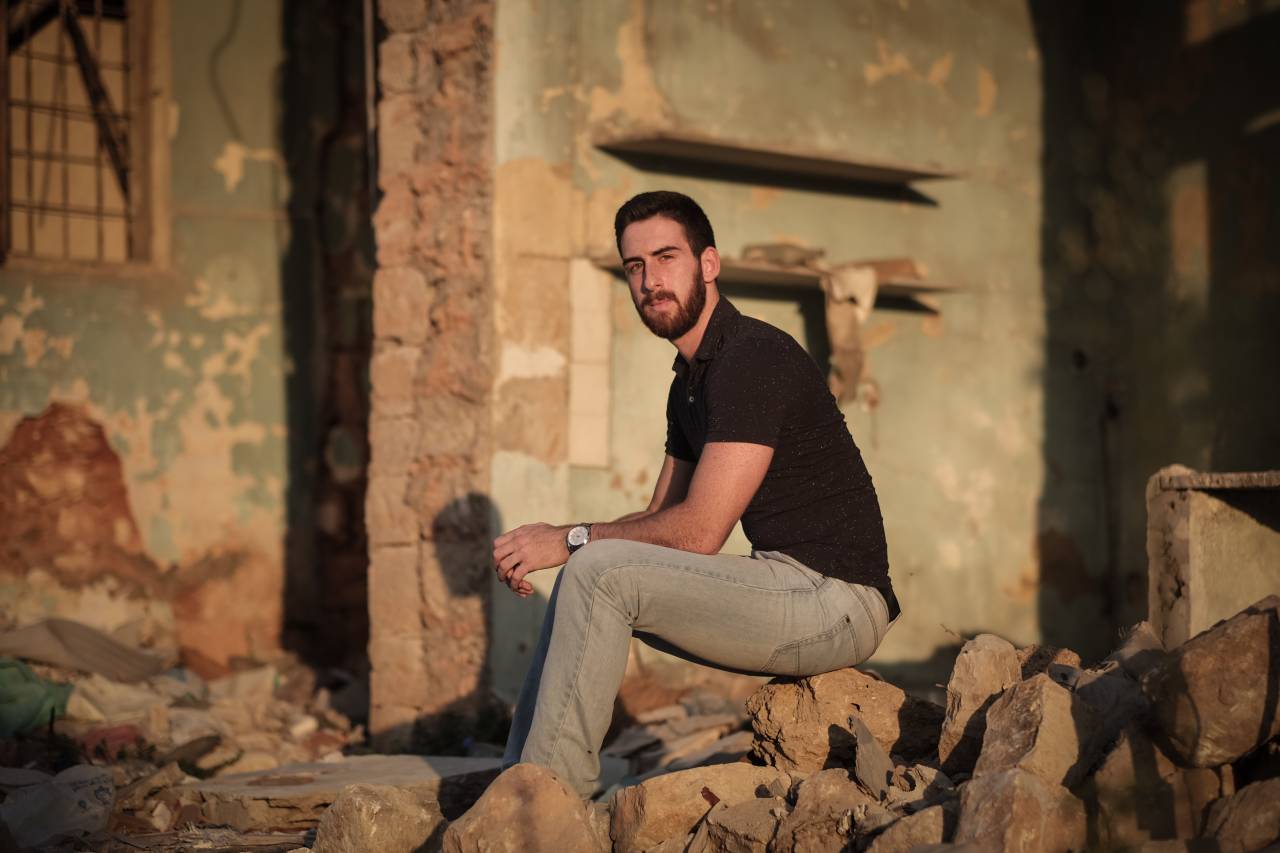

Moustafa Karout, who had been an active participant in the October 2019 protests, headed to Martyrs' Square the day after the explosion to help in the cleanup. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Moustafa Karout, who had been an active participant in the October 2019 protests, headed to Martyrs' Square the day after the explosion to help in the cleanup. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Moustafa Karout, 25, was at work at the City Centre mall in Hazmieh when he heard the explosion. “Suddenly the room started shaking, then it went silent for a second, then I heard this loud noise.”

Despite being relatively far from the blast, the mall was in a state of panic. Karout recalled “people running pushing one another, some on the floor, others crying. They didn't know what was happening.”

It was only after receiving videos of the explosion via WhatsApp that Karout realized the extent of the devastation.

Karout had been very active in the October 2019 thawra (revolution) street protests. “My first thought was, I want to clean the area where the thawra took place,” he said.

His own house in Hamra sustained only a few broken windows. The next day, armed with a broom and shovel, he hit the streets with other volunteers at Martyrs’ Square.

“You can imagine the chaotic situation, and people were a bit lost,” Karout said. “It was more like organized chaos.”

The vista at Martyrs’ Square was an unsettling contrast to the joyful scenes he had taken part in during the protests almost nine months earlier. He bumped into many people he had seen in the streets during the thawra, now driven by a similar urge to help in the wake of the disaster.

“We didn't have words to speak to each other, just hugs and well wishes, you know?” Karout said. “We had nothing to share, nothing more than that, because we still hadn't wrapped our minds around what happened.”

The day after the blast took a toll on him.

“The first time I cried was at night after I finished cleaning up on the first day, when we were going through the city and we passed by the port,” he said. One particular moment got to him, seeing blood on the cars along the roadside, as the smell of death wafted off of them.

Despite the heat and fears of COVID-19, he says everyone was “working through sweat, tears and blood to remove debris … Everyone felt horrible, but no one cared.”

He would continue to go down every day until Aug. 8.

Rami Chahine sitting inside an abandoned building in Mar Mikhael damaged by the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Rami Chahine sitting inside an abandoned building in Mar Mikhael damaged by the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Rami Chahine, 21, then a trainee nurse, was at home in Hadath watching TV when the explosion happened.

Like others he felt his building shake, but the house was undamaged.

“I got so worried that a generator might have exploded or something,” he said. The reality was much worse.

After turning on the news to see footage of the explosion, he called his mother and brother, who were both in Ashrafieh. They were safe, despite their close proximity to the blast.

The next day, Chahine headed down to Beirut to be part of the clean-up, also bringing special purpose bags and gloves and other tools to use in the efforts.

“What pushed me to volunteer is of course as a human I had to offer my help,” he said.

He began making the rounds in Ashrafieh with other local volunteers, to clean up the mess. While he was able to help out with sweeping the mounds of glass and clearing the rubble, he felt helpless seeing how great the needs were. Seeing people forced out of their homes or talking about loved ones killed and injured was “really hard to witness, to be honest,” he said “when I couldn’t personally offer any help.”

For the next three days he helped clear glass and rubble on his own in Ashrafieh and Mar Mikhael and also assisted in the cleanup at the local hospital where he was interning.

Ramy Hayek went from working in the Gulf to volunteering full time as an architect in the aftermath of the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Ramy Hayek went from working in the Gulf to volunteering full time as an architect in the aftermath of the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

Ramy Hayek, 30, was planning to go out with his friends to Gemmayzeh at around 7 p.m. His friends had arrived early, and he was running late, finishing up a TV show: this may have saved his life.

The restaurant where his friends had arrived before him was hit hard by the blast. Meanwhile, Hayek, whose home is above Antelias and far from the site, was uninjured.

“I was late to get there, and unfortunately they got badly hurt,” he said.

The next day, he went down to Beirut to help a friend salvage her apartment in Gemmayzeh and close it off against theft.

What led him to volunteer was the sense of injustice, he said.

“You cannot just sit and watch people suffering. You know that you can help and you have the time to help, and you're able to help.”

In the following days he started helping with the clean-up through a local NGO he encountered, Offre Joie. Having worked as an architect in the Gulf before the COVID-19 pandemic, Hayek’s technical background was an asset to the rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts in Karantina and Mar Mikhael and so he was assigned by the NGO to do assessment reports on the buildings.

Eventually he rose through the ranks to become Offre Joie’s project manager in the efforts to rebuild Karantina and parts of Mar Mikhael.

The biggest hurdles, he said, were “seeing all the destruction and not knowing where to start, because you look at so many buildings destroyed and, from a technical point of view, you need to start to stabilize the structures so nothing falls and kills someone, and then you have another tragedy on your hands.”

Particularly disheartening was “to see the people living outside their homes, waiting for any opportunity to get basic needs, like electricity and water…. And you can see the trauma in their eyes, something difficult to witness.”

At the same time, he said, “Working side by side with people, with the same mentality and goals … was something exciting, to also, meet new people, to see that you share a lot of common ground with a lot of people, kind of, in a way, gain friends and family that you never expected.”

After 15 months of work there, he developed bonds with the beneficiaries, some of whom he remains in contact with on a personal level to this day. He still visits Karantina from time to time to check in on everyone he met there.

Catherine Otayek is now pursuing her Master's degree in theater in France. (Photo by Ségolène Ragu)

Catherine Otayek is now pursuing her Master's degree in theater in France. (Photo by Ségolène Ragu)

Catherine Otayek, 27, was at home in Beit Meri on the day of the explosion.

“I remember feeling my bed moving, and I ran to the window, because I heard a sound and I thought there was an accident in the streets under my house,” she said.

She was on a call with a friend, and the internet cut out.

“I remember after that sitting beside my mom, watching TV and this was when it hit me,” she said. “The images were like an apocalypse.”

The head of Offre Joie sent out a message to all former volunteers: “Get ready. Tomorrow we're going to be on the ground.” Having been involved with them before on other projects, she answered the call.

“I never wake up early, but I would wake up at 6:30 a.m., get dressed, take my car, go to Karantina and be there at 7:30 a.m.”

In the weeks to come, she along with the team she led would serve 500 meals twice a day to Offre Joie’s volunteers as well as to local residents whose kitchens were destroyed in the blast.

“And for, like, two months we were just like robots,” she said, reporting daily to Offre Joie’s chantier, or work camp. “I was breathing the chantier, eating the chantier."

Where are they now?

Two years after the blast, Karout is in Qatar, working in marketing. Chaine is a nurse at a local hospital in Beirut. Hayek is still in Lebanon, and working for an international NGO as an architect. Otayek is now in France completing her master’s degree in theater.

For some, the explosion drove them away from Lebanon, for others, it opened up a new path within their country.

Four days after the explosion, on Aug. 8, Karout joined others in the streets to let out the pent up anger at the situation he had seen on the ground.

The security forces “started shooting at us, and I got hit in the face with around six to seven metal pallets,” he recalled. “One of them hit very near my left eye.”

The Red Cross was able to remove some of them, he said; some are still lodged in his face.

For Karout that was the last nail in the coffin, and he would soon depart to Qatar to work.

“I got so close to being permanently injured that I promised myself that I will never do anything for this country ever again, no matter what happens,” he said. “... I love everything about this country. But I also know that this love is not good for you.”

For Hayek, on the other hand, the blast sent him on a nearly opposite trajectory, leading him to transition from corporate work in the Gulf to humanitarian work in Lebanon.

After more than a year of volunteering to help rebuild the worst affected areas, he landed a job with an international NGO where he can apply his technical background as an architect.

“The thing is, I've always wanted to go into the humanitarian field, but you know, you get dragged into that corporate company life,” he said. After the explosion, “I thought to share all the experiences that I gained throughout the years into one project. It was a devastating project, but it got me into this field.”