Ariana Papazian signs a copy of her book at the launch event in Beirut on April 2, 2022. (Courtesy of Turning Point)

BEIRUT — Two months shy of her 16th birthday, Ariana Papazian had dreams, ambitions and problems common for anyone her age.

She had moved to a new school a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit and spent the next several months in quarantine adapting to the new environment, made more complicated by the shift to online learning. It was tough, but her life was about to get much tougher.

Nothing could have prepared Papazian to lose her mother, Delia, in the Beirut port blast on the evening of Aug. 4, 2020.

Time had stopped, the air was solid; it smelled of chemicals, ashes and death. When a thunderous sound deafened the streets of Beirut, no one could comprehend what was happening. Papazian’s family, like most of the city’s residents, had no idea that an unfathomable amount of explosives had been stored for years at the port in the city center, and now it had exploded.

“I was trying to stay still, not to fall. I was holding my friend’s and my brother’s hands while closing my eyes, turning my back against the smoke and holding my breath,” Papazian would write of the blast’s moment of impact..

In a moment of panic and absolute chaos, an overwhelming state of singularity and bitter loneliness, Papazian found herself making a decision between evacuating the building with her friend and her brother or holding on to her mother’s lifeless body — which she found lying on the floor of what was once their home, now completely demolished by the blast.

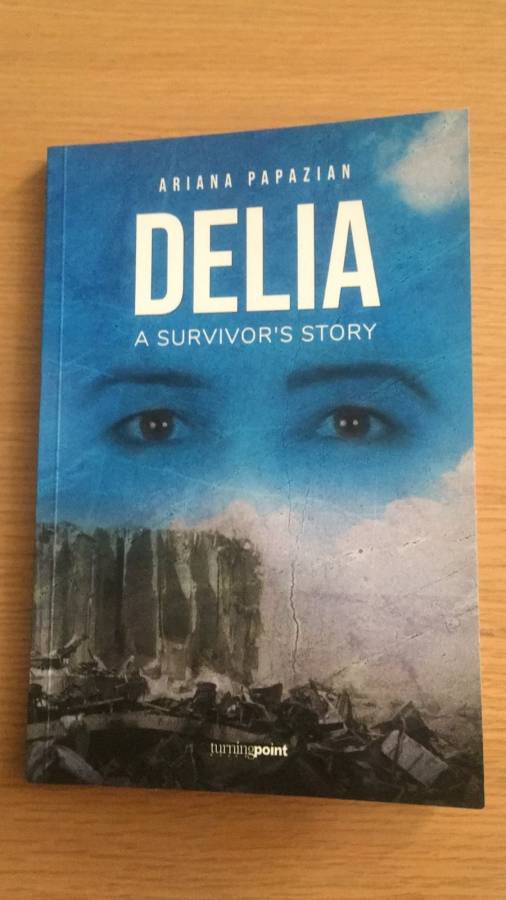

This month, nearly two years after tons of unsecured ammonium nitrate detonated, destroying much of Beirut, and the rest of the country in its economic and political aftermath, Papazian released a book entitled Delia: A Survivor’s Story about her own experience, detailing the emotional devastation caused by the cruel and abrupt manner in which her mother was killed and her own life after that tragic loss.

“I am a copy of my mother, [in] a lot of ways. I look exactly like her…, and personality-wise as well. She used to tell me that she raised me like her. The perfectionism, the ambition, that came from her,” recalled Papazian in an interview with L’Orient Today.

Delia encouraged her daughter to “look outside the box,” telling her that “the best thing you can do is have some experience, which is much more important than just grades.”

The summer of the explosion, Papazian had finished 10th grade at the top of her class, was preparing to attend the Oxford Summer Camp program, among other extracurricular activities, and was beginning to write a book, supported by her mother, on science and the mechanisms of the world. The project came to an abrupt halt after her mother's death, Papazian explained, as “it made no sense to continue this without her.”

Despite the void her mother’s death created, Papazian recalled the “brave face” she had to put on, stepping up to her new responsibilities, taking on a motherly role with her 9-year-old brother and providing as much comfort as she could to her family — as they had also suffered the loss of a daughter, a sister, a friend, a confidante, a hard-working woman who was calm, loving and fun.

Grief manifests itself in many different forms. For Papazian, she felt a strong urge, sometimes a responsibility, to stay positive and optimistic with a mindset that life moves on. Her way of grieving, however, clashed with the strict traditional Armenian-Lebanese manner that her family thought was the right way of honoring Delia’s abrupt death.

In the book, “I talked about my first Christmas and a bit about my interaction with my family. [They were] really closed up, each person was living in [their] own grief, and own sadness. And they didn't pay attention to me, they weren't seeing how hurt I was because I used to put on a brave face,” said Papazian, pondering her family dynamic at the time.

“I’m not a person who shows emotions a lot. So when I hid my feelings and my emotions, [my family] thought that I was really strong,” she said.

Sometimes other family members, in their own grief over her mothers’ loss, seemed to forget that Papazian and her brother had not only lost their mother but gone through the trauma of witnessing her death.

“My brother and I were facing [the consequences] directly,” she said.

Ariana Papazian with supporters at her book's launch event on April 2, 2022. (Courtesy of Turning Point)

Ariana Papazian with supporters at her book's launch event on April 2, 2022. (Courtesy of Turning Point)

While Papazian’s family was “blinded by grief,” she said, she turned to her close friends who showed her endless support and gave her ample space to mourn her loss as she felt was right.

Papazian had taken to journaling since she was much younger, especially since she speaks five languages — English, French, Arabic, Armenian and German — and needed somewhere to practice. After the explosion, Papazian left her home in Mar Mikhael and relocated with her father and young brother, leaving most of their belongings behind, and her journal became a safe haven.

“I started writing my thoughts on my computer, because all I had in hand were my laptop and my phone,” explained Papazian. “So for months, I wanted to jot down my ideas. I couldn't express my emotions and thoughts. I felt like I was frozen a certain way. I didn't know how to communicate what I was feeling. So I wrote down everything on my laptop.”

During that time, she penned her emotions on the first Christmas, first birthday and first Mother’s Day spent without her beloved mother. Paragraphs became pages and those pages accumulated, privately carrying detailed descriptions of Papazian’s personal experiences that she dared tell no one.

“Then I was inspired to write the book,” she said. “Actually, when I went to my therapist for the first time, she handed me her book, [one] she wrote about her experience during the Civil War, and I read it.”

After that, Papazian began the process of editing and compiling her journal entries into a complete manuscript, which she later presented to the Lebanese publishing house, Turning Point.

“As time went by, my book progressed and I was talking to my family about it, they got around the idea that no, I didn't forget my mother. It's not that I'm enjoying my life, forgetting all about the experience. But it’s a way for me to cope,” Papazian told L’Orient Today.

“The first time I read the manuscript, I had tears in my eyes. I couldn’t even read it in one go. It was really heartbreaking,” said Eleena Sarkissian, the editorial director at Turning Point, who worked closely with Papazian.

Despite the emotionally charged topic, she said, “We had to put emotions aside and get technical, looking at the structure, the flow, the text and the continuous voice.”

Drowning in the “what ifs” and the “I wishes” of her mother’s sudden, painful departure, Papazian frantically went over every detail of that fateful day, desperately trying to make sense of the explosion, her mother’s brutal killing and what it meant for her and her family’s future.

“There are many coincidences that happened on that day. For example, I was supposed to travel with my mother to London on the fourth of August in the morning, because I had summer camp at Oxford University. Due to COVID, the trip was canceled,” Papazian said, revisiting the details. “Imagine if they didn't cancel it. But then, maybe my father and my brother were going to be home, maybe we would’ve lost them.”

“There are a lot of questions that come through my mind. I can't find answers to all of my questions. The book was a way to find some and come up with conclusions.”

Victims and their families have yet to find peace or any sense of closure, as the exact cause of the detonation is still under investigation — one that has caused endless political, economic and social conflicts in the country.

“My brother, he doesn't understand the meaning of death yet. He doesn't understand what is happening,” said Papazian. She added, “We can't find closure yet. I don't know who did it. I don't know why it happened… I don’t know who to blame or for what.”

Grieving through art

Papazian is not the only survivor of the blast who took to some art form as a form of expression, grieving and therapy. In the aftermath of the blast, Lebanese citizens, diaspora and people from around the world wrote as a way to grapple with their pain and find solace, even if limited.

Lina Mounzer, a Lebanese writer and translator, published a guest essay in the New York Times, about the personal reflections from victims of the port blast.

She wrote: “In Lebanese Arabic, there is a saying: “The world stood up and sat back down.” It’s meant to describe chaos — a world turned upside down. This is what happened on that day almost one year ago, when Beirut was devastated by an explosion at a port warehouse. Everything slid out of place, and we’ve been unable to return anything to where it belongs… I am a writer — but I have often found myself at a loss for words since that day when thousands of tons of ammonium nitrate, knowingly left to deteriorate for six years in Hangar 12 at the Beirut port, caught fire and detonated in an explosion more powerful than the one that destroyed the Chernobyl nuclear reactor.”

Similarly, Rusted Radishes: Beirut Literary and Art Journal, edited and designed by a staff of AUB faculty, students, and alumni and others, published two different editions dedicated to the blast. The first edition was Issue 9, on health and illness, which was published almost seven months after the explosion, but was originally not intended for that purpose.

The staff put out a call for submissions early on, but had never anticipated the sudden emergence of the pandemic or the tragic explosion that came soon after. And so the opening for submissions was extended, allowing those affected by the blast to process their losses and emotions through art, most notably an article by the head of the emergency department of ABMC.

Writers in Response, the second project, was a collaborative effort formed into a web series and published by Rusted Radishes as a direct response to the port explosion.

“There's been a lot of expression on different platforms; there’s been a lot to say, over the past couple years. A lot of people were writing on their social media pages and that was important that people were sharing. [However,] social media posts live somewhere on the internet, but they don't get the attention that they need in the long term,” explained Rima Rantisi, the founding editor of Rusted Radishes.

The presence of published work, she said, both in print and even online, cement people’s words, emotions and experiences as a permanent part of history, “a sort of historical texts, that describe experiences, feelings, challenges, conflicts and an art form in response to that time.”

Rantisi added, “Literature and arts in general are the first things that slip through the cracks if nobody takes care [of them]. In times of catastrophe, the important thing is to [support] people who need food and basic [necessities] and so art and literature are always considered to be this kind of extra… But after the dust settles, we have to also make sure that what we built can survive as well.”

More than 20 months after the country was shaken to its core, healing has come with time for some. For others, to heal from such a tragedy, to move on with life while no justice has been served, no conclusions reached, no reparations provided, is wishful thinking.

“I did a time lap into the future; imagining my life without my mother and all her positive values and her joy of life. I knew I would not see her smile, her tears, and her pride in me if she left me. What would I do without her? How was my family going to fill the emptiness? What would this mean to me? My role in the family? How would I feel? How would I be treated? How could I go on with my life?” wrote Papazian in her book.

“I would have loved to learn more about her, like her teenage years, where I am now. I'm 17, about to turn 18. I really want to know what her experience was at my age,” Papazian told L’Orient Today with a wide smile on her face as she imagined her mother as a youngster.

She won't have the chance to hear all of her mother's stories, but Papazian said she can “speak up for what is right."

“I feel like there are a lot of people who still remain silent, they feel scared, they feel threatened by an outside force, or for some [other] reason,” she said. “I don't want people to start forgetting the explosion. We shouldn’t just protest or speak up [on the fourth of every month]. We need to do that every day. And that’s what I’m doing. Every day.”

The book is being sold at Aaliya’s Books, Librarie Antoine, Halabi Bookshop and via Buy Lebanese.