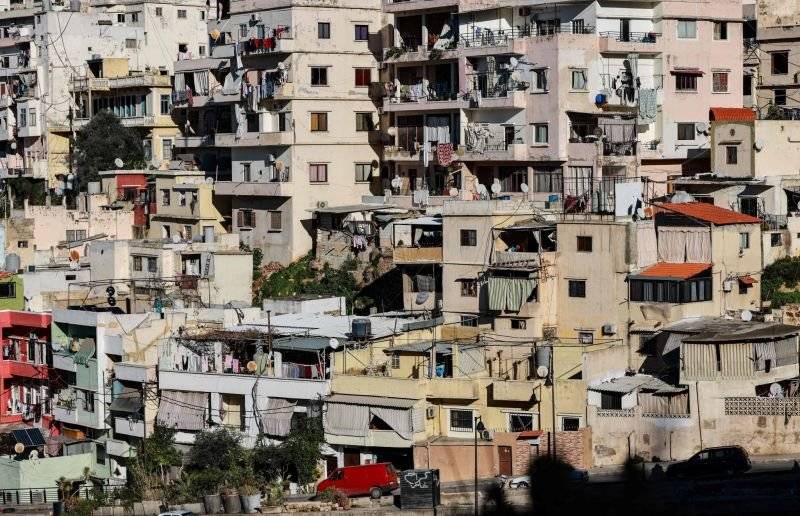

A residential neighborhood in Tripoli. (Credit: Joseph Eid/AFP)

The bare walls of Tripoli city, which usually abound with the candidates’ photos during elections season, speak volumes about demobilization in the North II constituency that comprises the Tripoli and Minyeh-Dinnieh districts.

In the shadow of a terrible economic crisis, the protagonists’ lack of means has certainly a lot to do with it, but it does not fully explain the dearth of elections fever in this region, especially in the capital of the North, which was at the heart of the Oct. 17, 2019 protest movement.

In this constituency, where the Hariri camp and its allies have a majority, confusion prevails a few weeks before the elections. This is not only because Future Movement head Saad Hariri has withdrawn from political life and Prime Minister Najib Mikati, another emblematic figure of the city, has also decided not to run in the elections, but also and mainly because an amalgam of choices is offered to voters. Some 11 lists will compete for the 11 seats in the constituency (eight Sunni, one Alawite, one Greek Orthodox, one Maronite), many of which share a very similar political line.

Concerned parties

The voter does not know which way to turn given that there are four lists representing the old order — a list concocted by former MP and vice president of the Future Movement Mustapha Alloush; a second list sponsored by Mikati; a third list chaired by former minister Ashraf Rifi; and a fourth list involving Faisal Karami and the pro-Hezbollah camp.

A fifth list consists of the Jamaa Islamiya and includes independents. The six other lists supposedly represent new groups, including those stemming from the protest movement.

“The traditional forces declined [in popularity] and the new forces are disparate. On the popular level, no major movement has emerged in Tripoli, which makes the public opinion’s mood very volatile,” said Mohammad Kabbara, a professor of political science at the University of Balamand.

Although prognostications indicate that some figures representing civil society have a chance to secure seats, the real battle is between the four main lists representing the traditional movements, including former Future Movement figures who will cross swords.

The Mikati-backed list managed to bring on board Abdel Karim Kabbara, the son of Mohammad Kabbara, who has been affiliated with Hariri for years, and Suleiman Obeid, the son of former minister and MP Jean Obeid, a prominent figure in North Lebanon, who died last year.

One of the two other lists is sponsored by Mustapha Alloush, who was a key player in the Future Movement before resigning, and the other by former minister Ashraf Rifi, who broke away from the Future Movement a few years ago and advocates a more radical stance towards Hezbollah. The Rifi-backed list is supported by the Lebanese Forces. The two lists will also compete with each other by attracting votes from the same circles of ballot castors.

On the other side, the opposition lists abound. There is a list chaired by Omar Harfouche, an expatriate businessman and controversial figure who made his fortune in Paris and Kiev. Another list is sponsored by the founder of Citizens in a State, Charbel Nahas.

A third list includes a candidate from the National Bloc and several figures from the protest movement. The last two lists include all those who were not accepted to be on the other lists and who still want to run in the elections.

While mere months ago voters in Tripoli — referred to as the bride of the revolution in 2019 — were expected to mount the biggest challenge to the establishment parties, this is certainly no longer the case today.

“One must admit it: the climate imported by the popular uprising has not succeeded in permeating Tripoli’s neighborhoods. It is the traditional forces that have the strongest chance of breaking through today,” said Mohammad Alloush, a university professor from Tripoli.

From 2018 to 2022

In 2018, the list sponsored by the Future Movement (The Future of the North) won five seats with 51,937 votes, in an election where out of the 343,061 registered voters, only 38 percent cast their ballot. Mikati’s list obtained some 40,000 votes, but failed to get the Sunni candidates that were on it elected. He was thus perceived as a representative without Sunni legitimacy.

Rifi, for his part, was completely eliminated from the game, having failed to obtain the electoral threshold of 13,311 votes.

It is therefore among these three lists that Hariri supporters will distribute their votes. Some of the Hariri supporters, who are bitter because of his withdrawal, could also abstain from voting.

There is greater risk for a candidate like Ashraf Rifi, whose decision to ally with the LF is frowned upon in Tripoli.

LF leader Samir Geagea irritated Hariri’s hard-line supporters when he bet on attracting Sunni votes after Hariri’s withdrawal.

Discreetly supported by former Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, who was criticized for having decided to oppose Hariri’s decision to boycott the elections, Mustapha Alloush does not want to further irritate the Future Movement’s sympathizers, telling anyone who will listen that he is not directly supported by Siniora, and even less by Saudi Arabia.

Main issues

Dispersion of pro-Hariri electorate: Many Tripoli observers agree that none of the protagonists, especially among the old order, has a clear political line or orientation in this election, and this risks making this battle quite flavorless.

“Worse still, no one, not even the forces known for their fierce opposition to the moumanaa camp (the pro-Iranian axis), has a clear strategy in the face of the main problem: the risk of seeing Hezbollah’s stranglehold on the state firmly established in the event that the pro-Hezbollah camp win across the entire country,” said former minister Rachid Derbas, who is close to the Future Movement.

One must recognize that the pro-Hariri public opinion is divided and the scattered votes will ultimately benefit the opposing camp, many experts said.

Hezbollah and its allies are accused of having succeeded in swallowing up all areas that vote against them, including the predominantly Sunni ones, by imposing solid coalitions that will seemingly win. This is notably the case in the North II constituency with the Karami list.

On the other hand, whether the list is affiliated with the March 14 camp or the protest movement, the general finding is that of a dispersal.

The question on everyone’s lips is the following: How to explain division between the three main lists of the opposing camp, namely those of Mikati, Alloush and Rifi? “One of two things: either foolishness or [political] gamesmanship, or both at once,” Derbas said bitterly.

The Greek Orthodox and Alawite vote: On Karami’s list, there are two jokers who will maximize the chances of his list.

Taha Naji of the Ahbash, who can win some 5,000 votes, and Rafli Diab, who is running for the Greek Orthodox seat and is said to be able to attract a majority of the votes in this community.

The list also includes another strong Sunni candidate — Jihad Samad. Karami could also count, in theory, on a large part of the 17,000 registered Alawites (5 percent of the voters) who traditionally vote for his political line.

However, it is Ali Darwish, the Alawite candidate on the Mikati-backed list, that the odds favor. Also on Mikati’s list, the son of Mohammad Kabbara will be able to take advantage of the 9,600 votes obtained in 2018 by his father who ran on the Future’s list.

Another well-positioned candidate also on this list is Kazem Khair, who is able to obtain 6,754 votes, as in 2018.

That leaves three Sunni seats to be secured by candidates, including Mustapha Alloush and Sami Fatfat, who scored 7,300 votes in 2018, and Ashraf Rifi, who obtained 6,000 votes in the 2018 election.

A seat could perhaps go to a second Sunni candidate on Alloush’s list, which attracted prominent figures from academic circles, independent candidates and from the protest movement.

Datasheet

Two districts: Tripoli, Minyeh-Dinnieh

Eleven seats to win (eight Sunni, one Alawite, one Maronite, one Greek Orthodox)

Number of registered voters: 341,534

Voters’ sectarian distribution: 84 percent Sunni, 5 percent Greek Orthodox, 5 percent Alawite, 4 percent Maronite, 1 percent Shia, 1 percent other

Number of registered voters abroad: 37,714 (6 percent of registered voters)

The competing lists

1- Dawn of Change: formed by groups close to the protest movement

2- Capable: Citizens in a State (Charbel Nahas)

3- The Real Change: Jamaa Islamiya

4- Rescue of a Nation: Ashraf Rifi and the Lebanese Forces

5- Ambition of the Youth: Independents

6- The People’s Will: Faisal Karami

7- The Third Republic: backed by Omar Harfouche

8- Revolt for Justice and Sovereignty: protest movement and National Bloc

9- Lebanon is Ours: former pro-Harari figures (led by Mustapha Alloush)

10- For the People: backed by Najib Mikati

11- Stability and Development: protest movement groups

This article was originally published in French by L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.