A portrait of photogrpaher Mohamad Abdouni (Credit: Pauline Maroun)

BEIRUT —The Lebanese-born Mohamad Abdouni is an ambidextrous creative force — a photographer, filmmaker and curator based between Beirut and Istanbul. He is also editor-in-chief and creative director of Cold Cuts magazine, a periodical photo journal that explores queer culture in the Southwest Asia and North Africa (SWANA) region, and is preparing to publish a book of photographs and oral histories from the trans community in Lebanon.

In a region where queer narratives and histories have often been erased or neglected, portrayed as a product of the West, and where homosexuality is widely criminalized, projects like Abdouni’s serve as a haven for queer people, where “our stories, histories and the culture we produce can be collective and accessed,” said Marwan Kaabour, a Lebanese, London-based graphic designer and the founder of Takweer, an online platform exploring queer narratives in Arab history and popular culture.

“It is an act of resistance that ensures people are aware of our presence and our contribution … It is also a space for young queer Arab kids to feel a sense of belonging, that people like them existed in our part of the world since as long as history has been documented.”

On a balmy Saturday afternoon in Beirut’s Badaro neighborhood, Abdouni sipped an espresso, wincing at the jubilant noise of a traditional pre-wedding zaffe from another street close by. He dissolved a tablet of Vitamin C in a cup of water, attempting to calm what he described as a massive headache, as he pondered the journey that led him to photography.

Growing up in Tariq al-Jadideh, Abdouni says his family was “poor,” although that didn’t stop his parents from pushing burdensome boundaries to enroll him and his siblings in one of the most acclaimed and elite schools in the country, Collège Notre-Dame de Jamhour in Baabda.

“Spending your day at Jamhour, but then spending your life in Tariq al-Jadideh, that kind of gives you quite an interesting scope on the disparities of life,” Abdouni said.

The summer before his first year of college, he bought a 35-millimeter camera from a flea market. His interest in photography at the time, he said, was partly driven by a fear of forgetting.

“I’m always afraid to, at one point, no longer remember the people, places or certain feelings I felt at certain moments. I’ve had, I always have this looming fear that I will forget them,” began Abdouni.

He explained that he quickly realized the camera could soothe this fear, and after that, he said, “I just never let it down.”

After graduating from college, obtaining a degree in fine arts and communication arts, Abdouni worked as a comic artist for a while, an art director in different design studios and was even a curator for exhibitions.

For the first 10 years of his love affair with the camera, Abdouni wouldn’t take professional photos, only capturing moments from his daily life. In retrospect, he thinks that his professional career as a photographer today just happens to be a “very beautiful coincidence that resulted from that fear [of forgetting].”

At one point, he said, he began publishing some of his photos on Instagram.

“At that time, I was already taking portraits of the queer community at their events, because I was just interested in gathering and documenting what was happening then,” Abdouni told L’Orient Today. The photos, he said, “garnered attention very quickly, maybe because at the time there wasn’t necessarily anyone that was heavily documenting and sharing images about the queer community, which is not the case today, obviously.”

His photography hobby eventually developed into a full-fledged career, creating work that has been exhibited at the Foam Gallery in Amsterdam, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris and in festivals around Europe. Abdouni’s work includes more commercial projects such as his fashion shoots for Vice UK, Vogue Italia, Gucci, Farfetch and L’Officiel, to name a few. On the other hand, his more personal ventures — documentaries and photo series featuring Beirut’s queer community — have also amassed global attention, both digitally and in print.

Balancing between more fashion driven, commercial work and personal ventures documenting his community, Abdouni says that he couldn’t imagine having one without the other.

“Both of them are very important for me because when I spend too much time on commercial projects, I feel so empty, vain. But when I spend too much time on the documentary work that I do, I feel very suffocated,” shared Abdouni.

Abdouni’s photography style is a melting pot of inspiration and curious aesthetics; highly romanticized retro lighting is, however, consistent throughout all his projects.

His pictures capture beauty of a strange kind. There is no peaceful or soothing comfort in them, at least not in a typical or traditional form.

Fellow Lebanese photographer Tanya Traboulsi, a friend of Abdouni’s, said, “He’s looking for the things that others might not look at … He guides your eyes to details that you may not want to look at and I find it very interesting and beautiful.”

Abdouni said his photography is inspired by the works of fellow Arab photographers, like Fouad Khoury, Clara Abi Nader and, of course, Traboulsi.

“I don’t want to emulate anyone’s work because I won’t have my own stamp. But I do find myself unconsciously [recreating] the work of some of my personal greats,” explained Abdouni as he rolled a cigarette.

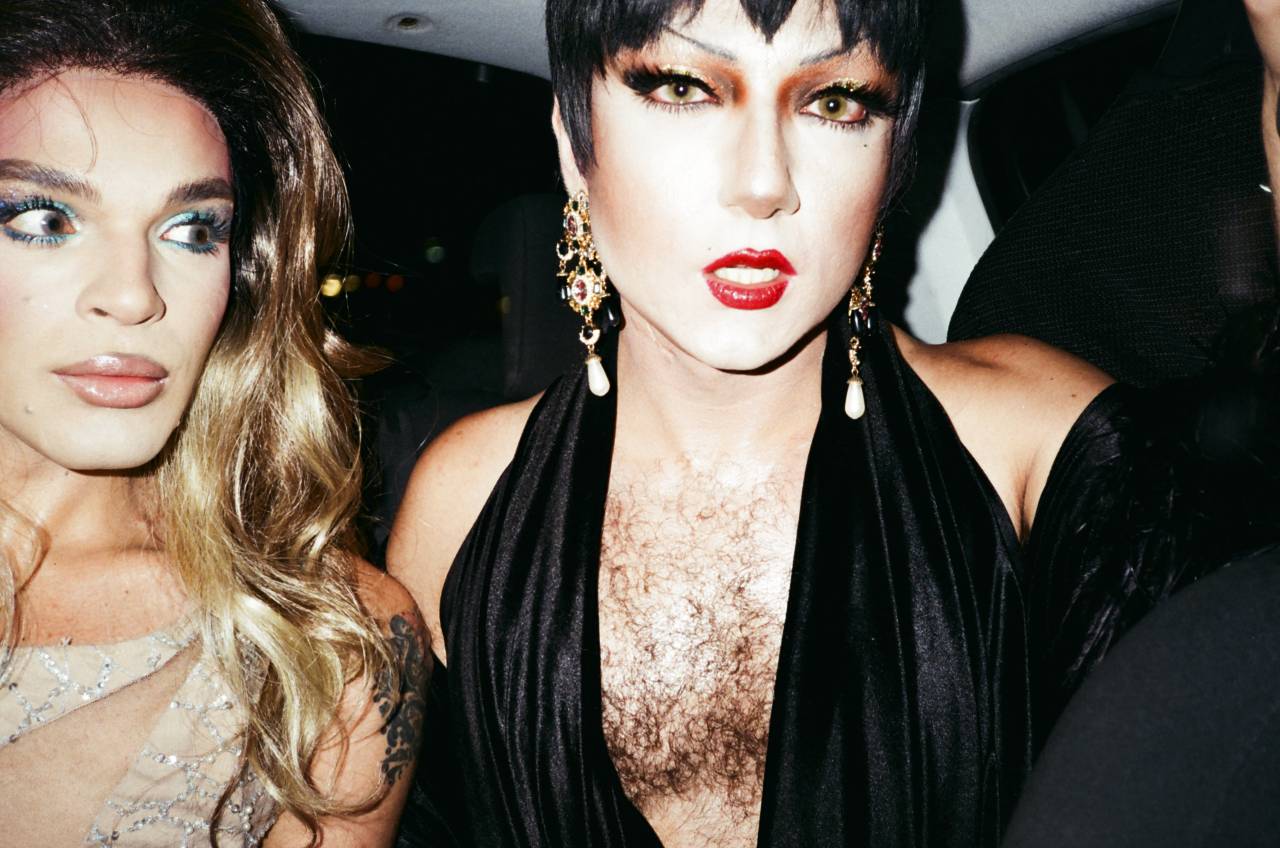

“Very recently, I took a picture of [two Lebanese drag queens] Anya [Kneez] and Andréa in the back of my car on the way to a wedding. Shortly afterwards, I stumbled across one of my favorite pictures that I hadn’t seen in a very long time taken by Nan Goldin,” Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a Taxi, NYC, 1991, wherein two drag queens are photographed at a close-up in the back of a yellow taxi. “I just recreated that picture, without necessarily [knowing] because it’s imprinted in my head.”

"Andrea and Anya Kneez in the back of my car," Beirut, 2021 (Credit: Mohamad Abdouni)

"Andrea and Anya Kneez in the back of my car," Beirut, 2021 (Credit: Mohamad Abdouni)

Working with marginalized groups such as the LGBTQ+ folks in Lebanon, where sensitivities are greater and the dangers inherent in exposure much higher, there’s already a lot of pressure. Abdouni says this particular kind of work feels heavy, but “a good heavy, a needed heavy.”

While a series of court rulings in Lebanon in recent years have held that consensual sex between people of the same sex is not unlawful, the social stigma remains. The queer community is still marginalized and largely at risk, their plight heightening amid the COVID-19 outbreak in the country and the tragic port explosion in 2020.

According to Abdouni, the criminalization of queerness is a nuanced and complex issue, as it takes different forms throughout the SWANA region, but even within various cities and towns within one country.

He says that being “bundled up into this one bag of the ‘Middle East’” is misleading. It serves to delete the numerous entities that exist within its scope, “it’s hundreds of different queer communities with different ways of doing things, different histories, different cultures, different everything.”

Abdouni’s drive to birth Cold Cuts came from frustration with the lack of accurate, substantial and dignified documentation of queer Arab history despite the rich culture of the community.

“I think, for me growing up, [it was] like, ‘What is my history? Who are my parents, my family? Who are my elders? Who are my role models?’” Abdouni said. “Because we had role models that come from like Western media, but there’s only so much you can relate to them.”

The first edition of Cold Cuts was released in 2017, featuring the work of over 30 creatives, photographers and performers gracing the publication’s 172 pages. Following its debut issue, Cold Cuts released the award winning documentary Anya Kneez: A Queen in Beirut. In Abdouni’s words, the short form documentary “offered a glimpse into the life of the boy who revived the drag scene in the clubs of Beirut, and toured international film festivals around the globe.”

The subject of the film, Charlie Nicola, also known as Anya Kneez, his drag persona, is also Abdouni’s best friend, who he has known for more than a decade.

The first time they met, Nicola recalled, “I brought my design portfolio thinking this person is gonna help me find a job.” Later, they often ran into each other at bars in the bustling streets of Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael. At the time, Abdouni would DJ at a bar called Charlie’s, and Nicola would often come “decked out to the nines” and end up dancing on the bar.

At one point, when Abdouni had moved back to Tariq al-Jadideh and was in the process of renovating his house, Nicola took him to a fabric wholesaler to look for a big bolt of fabric so he could create an at-home studio set.

“We bought a big bolt of white cotton shirting fabric that had a beautiful crisp drape to it. We lugged it back to his house and we started draping and playing with the fabric. He then told me to pose for him. I mean, you do not have to tell me twice to pose for Mohamad. I took all my clothes off and he shot me in the nude,” said Nicola.

“I had never felt more comfortable with someone more in my life that I let him direct me in every way possible because I trusted him wholeheartedly.”

The documentary was shot over a weekend in 2017 with Abdouni’s “little camera,” as Nicola was transforming into Anya before a show. A few months after that weekend, Abdouni secretly recorded him as they were having a conversation wherein Nicola explains how it felt to move from NYC, “a queer Mecca,” back to the Middle East. The recording was eventually coupled with the footage.

In 2019, a special edition of Cold Cuts, Doris & Andréa, was released simultaneously with the opening of an exhibition of the same name at the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris. The issue documents the lives of Doris and her genderqueer son Andréa, as they “challenge the social norms of a patriarchal society and the so-called family values of a Middle Eastern family.”

Abdouni said his work is never based on a particular intention. Instead, his projects are born authentically, in the spur of a moment, or by meeting a new person, something that spikes his curiosity or feeds into his frustration.

According to him, the magazine started off as a fun playground, a “projet caprice.” The editorial content eventually shaped up in an intrinsic inclination, which then organically grew into a queer-focused publication.

Abdouni’s most recent book, Treat Me Like Your Mother: Neglected Trans* Histories From Beirut’s Forgotten Past, released with Cold Cuts, navigates a collection of untold stories, archival images and studio portraits of 10 trans women living in Beirut. The inspiration for it came after Nicola attended a queer open mic night at the Haven for Artists venue in Beirut.

There he saw “Mama Jad,” a trans woman in her mid-fifties who told stories of how she had survived the Civil War in Lebanon.

“I was sobbing from beginning to end,” Nicola said. “The way she spoke about community still gives me goosebumps to this day.”

That night, Nicola hurriedly made his way to Abdouni’s home, narrating Mama Jad’s story to him, as they both cried “into each other’s arms.”

That night was the birth of “Treat Me Like Your Mother,” which was created with support from LGBTQI+ NGO Helem, the Arab Image Foundation and culture space Station Beirut.

"Dana for Treat Me Like Your Mother," Beirut, 2019 (Credit: Mohamad Abdouni)

"Dana for Treat Me Like Your Mother," Beirut, 2019 (Credit: Mohamad Abdouni)

Each of the women portrayed is between their late 30s and 50s, aiming to demonstrate not only their charged history in the (then) war-torn and complex country, but also drawing attention to their alienation, forced upon them by society. The subjects of the book were all paid, which is not typical in documentary or journalistic work.

Abdouni said that was because “we were told by Helem that the only way these women are actually going to give us time of day is” to pay them. “The women, almost all of them, came in kind of pushing back, like ‘I'm here to do what I need to do and get my money,’ because they’re used to that. They’re used to foreign [media] coming to get their stories of trauma and drama, and then leaving.”

The book, which is set to be released this year, is a transcription of unedited oral histories.

“You can tell in everyone’s interview, kind of like the pivotal point where they felt comfortable. I think that’s beautiful … This is a community that has only known being taken advantage of and not being appreciated,” Abdouni said.

Abdouni is one of a number of people working to deconstruct narratives around LGBTQ+ people in the region and to empower the community through visibility. Takweer’s Kaabour is another.

When Kaabour first encountered Abdouni’s work, he said, “I found it exciting, dynamic and inspiring.”

Takweer, an Arabized play on the English word “queer,” is also a platform that was born out of frustration with “the lack of accessible information about queer stories, identities and culture for people like myself,” Kaabour said. This dearth of resources pushed people like him and Abdouni to “look westwards to understand our standing in history, society and popular culture.”

“For the longest time, we could’t even talk about the very presence of queer people amongst us in the Arab region. I think that is one pretty huge taboo to break, by showing that not only do these people [exist], and here are their faces, their stories, their struggles, and their joys, but we are showing how we have always existed,” he said. “It’s in the words of Abu Nawas in the Abbasid caliphate, and in Youssef Chahine’s films, in Nancy Ajram’s videos, in our streets, families and nightclubs. It is also breaking down the farcical assumption that the Arab world has always been ‘conservative’ or that queerness is a concept that was ‘imported’ from the West.”