Tree stumps give away that some of the trees cut down in Akkar were still alive at the time of their felling. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

ANDAQIT, Akkar — Last year’s forest fires have left the hillsides of Akkar’s Aoudine valley charred and bald, with a jagged strip of green above marking the line where firefighters managed to control the blaze.

On a dirt road below, the only human visible is an elderly shepherd tending his flock, but there are clear signs of other recent human activity nearby: a discarded saw blade, an oil canister, and, most tellingly, the stumps of recently cut pine trees.

“This one, you can see it’s green — it was alive,” said Elias Fares, gesturing at one of the stumps. Fares is a hiking guide and civil defense and Red Cross volunteer from the nearby village of Qobeiyat, and one of a group of residents from the area who have been trying to stem the rise in illegal tree cutting.

So far, it is a largely futile effort. While the issue of unpermitted logging predates the current crisis, officials and residents of mountain areas, particularly in Akkar, say it has increased this year, driven by a combination of opportunity and need.

“The economic crisis has prompted citizens in some areas to cut down trees haphazardly and without turning to the Ministry of Agriculture to obtain permits,” Agriculture Minister Abbas Hajj Hassan, whose agency is responsible for overseeing forestry, told L’Orient Today. “This is really a shame, because we are, in fact, always discussing with the United Nations, the donor agencies and the European Union the need to have more green spaces in Lebanon.”

Hassan noted that his ministry fields “hundreds” of complaints daily regarding illegal logging but said they lack the manpower and other resources — including funds for fuel — to patrol all the forested areas and investigate all the complaints.

This winter’s storms have been unusually harsh, and with the skyrocketing cost of fuel — the official price of 20 liters of diesel is now LL333,600, while a public employee might make LL2 million or less a month — few can afford to buy diesel to fuel the old fashioned “sobia” heaters that are common in rural areas.

And since a series of devastating forest fires have torn through the mountains, particularly in Akkar, since last summer, many locals have flocked to the burned areas — some on public land, some on private — to gather wood.

Among them are Jamileh and Makhoul Semaan, an elderly childless couple in Qobeiyat. With state electricity a rarity, they now spend most of the day sitting in the dark to avoid burning precious diesel in their generator.

“No one in the house is working. We don’t have any income to live off of,” Jamileh said. “We used to use diesel for heating, but now we’ve moved to firewood, because we can’t get diesel.”

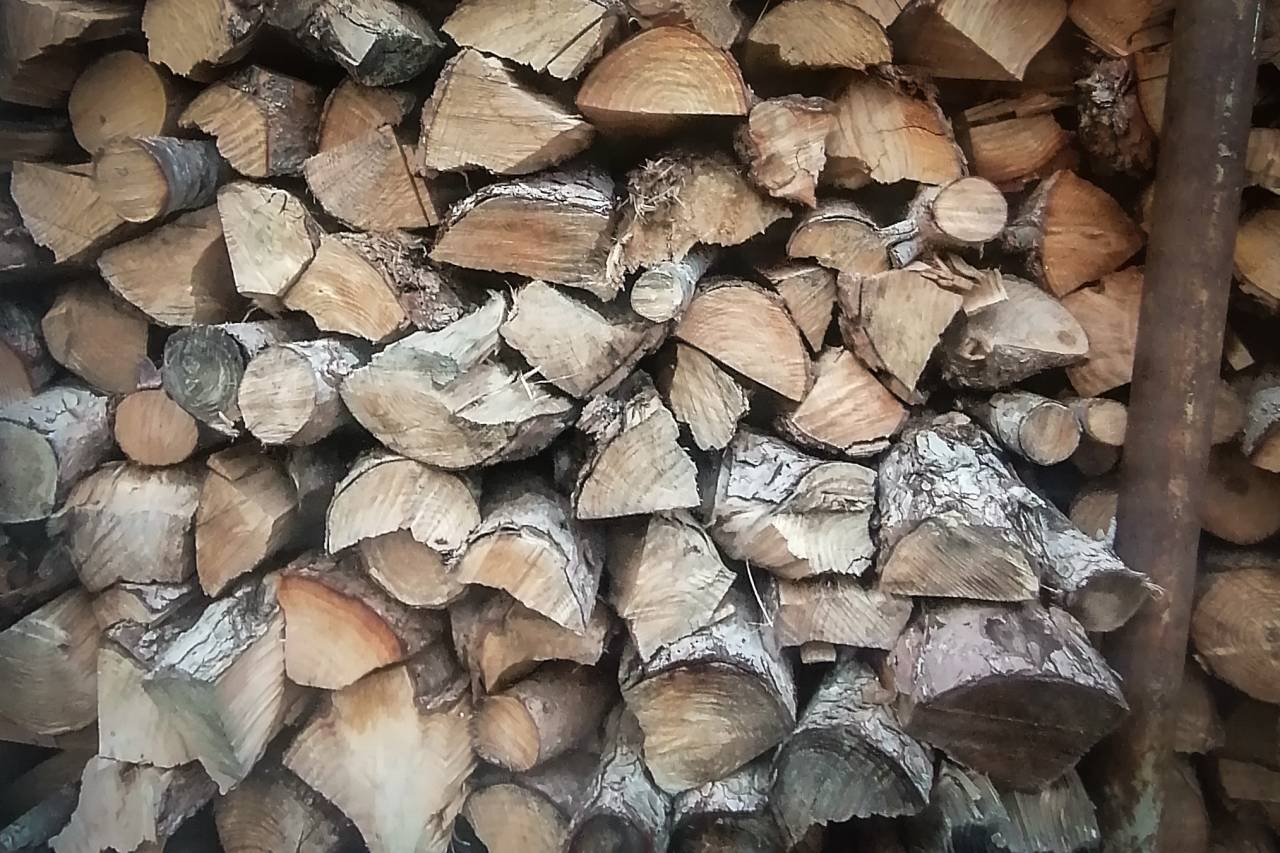

The log pile at Jamileh and Makhoul Semaan's home. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

The log pile at Jamileh and Makhoul Semaan's home. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

Makhoul, who has leukemia, can’t work in construction as he used to, but he has been able to collect firewood from the nearby burn sites. The wood piled up in the couple’s shed ensures that they can at least stay warm.

Fares said he is not opposed to people collecting firewood but to the uncontrolled manner in which it is taking place, without permits from the Ministry of Agriculture and with some taking advantage to chop down healthy 200-year-old trees in the green areas adjacent to the burns.

“We’re not against people benefitting from the wood, but in a way where they are not cutting down all the trees,” he said. “You can prune and protect the forest and at the same time secure heating. As our grandparents did, they could prune or thin out a tree that is going to fall, but in a way that will protect the forest.”

He added, “The problem is if you open up the opportunity, all the people who want to benefit from any crisis will come and cut trees to make a business out of it.”

Fares even suspects that some of the past year’s fires were set deliberately with an eye to create an opportunity for more logging. While there has been no official confirmation of that theory, Environment Minister Nasser Yassin said after a series of wildfires broke out around the country in November that some of them appeared to have been intentionally set and that the Interior Ministry was investigating the matter.

Fares said he is not opposed to people collecting firewood but to the uncontrolled manner in which it is taking place. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

Fares said he is not opposed to people collecting firewood but to the uncontrolled manner in which it is taking place. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

An Interior Ministry spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

In at least one case, the logging has had tragic results: a man from Andaqit was killed in September after his car rolled backwards over him while he was loading wood he had cut, Fares said. And disputes over logging escalated into a deadly exchange of gunfire between residents of the towns of Fneideq and Akkar al-Atiqa in August.

Given the lack of state resources to monitor the forests, local residents discussed putting together volunteer patrols, Fares said, but the efforts have fallen flat, largely due to the expense of fuel as well and the lack of funding to train volunteers and buy items like communications equipment.

If assistance with enforcement is in short supply, so is help with heating. International organizations have helped some institutions to procure fuel over the winter: UNICEF distributes fuel for winterization annually to schools in the mountains, and the United Nations also launched a program last fall to distribute fuel to health facilities and water stations, an “exceptional intervention” that will end soon. The supply of fuel to water establishments will end in February and the support to health centers and hospitals at the end of March. But there has been no widespread program to distribute heating fuel to individual families.

“Our role is not to take the place of the government,” UN resident Humanitarian Coordinator Najat Rochdi told journalists during a recent tour of some of the institutions receiving the aid. She added, “Our role is not to take the place of Electricité du Liban. We don’t distribute electricity, and that is the work of power companies. Our project for distributing the diesel is in the health and water sectors. We have not widened this [to provide fuel to households].”

Environment Minister Yassin told L’Orient Today that his ministry has been discussing with the World Food Program a project to to set up a number of manufacturing plants that would make heating briquettes from biomass that could be gathered from the forest and from agricultural byproducts like the pulp left from olives after pressing them for oil.

Using a similar concept, some of the grain that had been stored in the silos at the Beirut Port that was ruined in the explosion has been turned into artificial wood briquettes to be distributed to the Lebanese Army for its barracks in the mountains this winter.

“We're discussing with the World Food Program to fund these briquette plants and also other donors, including UNHCR, since this could also be a way to give refugees some of the artificial wood particularly now as you see, the prices of fuel are very high,” Yassin said. “And that will actually contribute to the winterization program. So we started the dialogue with them and with WFP … We hope by next summer, we will have a number of these plants around the nation” so that by the coming winter, they will be able to supply needy households with heating fuel.

But the assistance won’t come in time to take the edge off of this winter’s storms.

Back in the Aoudine valley, Salim Sabegh, the shepherd tending his flock, acknowledged that he sees a regular stream of trucks coming in and going out loaded with wood. He sees no problem with it.

“This forest, since it was created, really, it wasn’t cut. But the fires came this year … Why shouldn’t people benefit from it?” he said. “If you get LL2 million a month, what can you do with it today? If the generator and electricity costs LL1.4 million, can you live like this?”