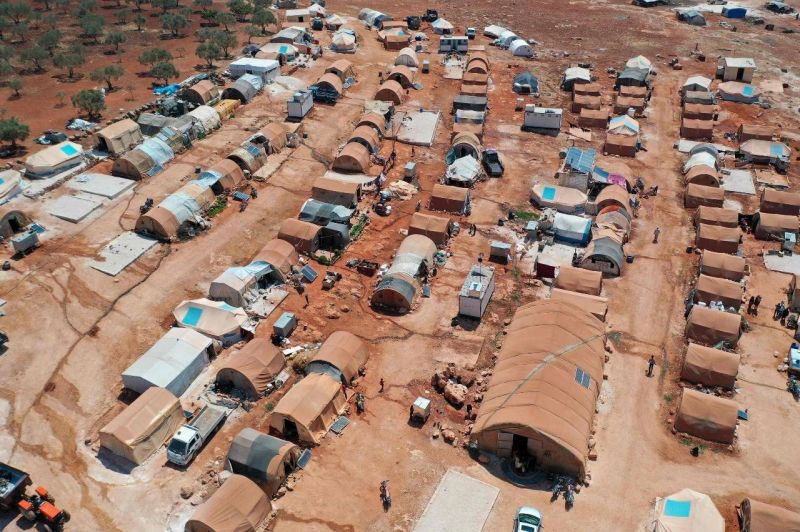

An aerial view of a camp for displaced Syrians from Idlib and Aleppo provinces, near the town of Maaret Misrin, northwestern Idlib Province, Syria, July 11, 2020. (Credit: AFP)

On May 28, 2021, the Syrian Arab Republic became one of the 34 executive board members of the 74th World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization through an uncontested procedure. Twelve of the 34 seats were available and 12 countries were put forward, Syria being nominated along with Afghanistan by the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office. No votes were cast and no dissent presented from sitting donor members although there was an opportunity to do so.

The admission of Syria is but one in a series of misjudgment and mismanagement in the humanitarian and diplomatic approaches to Syria and Lebanon. Over the past month, Lebanon has become a humanitarian and economic disaster — due to a cluster of crises feeding off each other, making the country unlivable. At times it appears that humanitarian operations in Lebanon seem unable to deal with the situation and their political counterparts in Beirut while people lose life savings and public services stop working, threatening public health and national and regional security, let alone the need to provide any stability for economic recovery.

UN agencies such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and United Nations Development Program were unable to reach a consensus as to what a humanitarian emergency looks like preferring instead to, call it a “crisis of governance.” On June 14, the UN’s deputy special coordinator, Najat Rochdi, stated in an attempt to shock Lebanese politicians into action that “the development of Lebanon is not the responsibility of the international community.” Over the past few weeks, there now appears to be some internal agreement to initiate an appropriate humanitarian response.

The previous Lebanon Crisis Response Plan, through which humanitarian aid is delivered, was extended for another year in 2021, but events on the ground clearly exposed early on how out of touch it was. Now there are a raft of overlapping policies and programs consisting of the LCRP, Lebanon Reform, Recovery & Reconstruction Framework (3RF), new response plans for health, nutrition, food security, education and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) with a new UN strategic framework under development in the background. How these are funded, implemented and properly coordinated remains to be seen. Budget cuts to humanitarian funds by major donors such as the United Kingdom, internal indecision and lack of influence on the Lebanese political system may mean it is too late to have a meaningful impact given the scale of the situation.

Since the beginning of the 2011 Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon, humanitarian coordination and management have been less than robust. There is a long trail of incidents highlighting an inability to effectively deal with local political systems, replication in humanitarian response policies and funding across agencies and donors and a lack of impact evaluation to see where aid money was spent and whether it actually had any discernible impact. More recently, both UN agencies and donors have appeared challenged in their ability to properly support an investigation into those responsible for offshoring millions of dollars of depositors’ money, as well as the siphoning of hundreds of millions dollars’ worth of aid money by local banks. There has been little forceful public response from the humanitarian system or donors.

Meanwhile, the regional health wing of the UN, WHO-EMRO, gives the impression that political decisions and military actions by governments in the region do not impact the population’s health. A major EMRO report on how to achieve health equity barely mentions the influence of politics, military conflict and attacks on health care facilities by its member states. Greater attention is placed on how economic sanctions by outside donor member states affect the regions health rather than continuous violations of international humanitarian law by Syria and their allies such as Russia in targeting health facilities and civilian populations, and the mass detention and systematic torture and murder of thousands of civilians.

Indecision and less than transparent political management by the UN in Syria are not new. In 2013, the handling of the polio outbreak by WHO Syria and EMRO was slow and ineffective and data from EWARS was not properly reported. This left opposition controlled areas with minimal or no vaccination coverage over the two preceding years of the outbreak. This situation is poised to repeat itself with glaringly low immunization rates across non-governmental areas of northeast Syria, particularly eastern Aleppo. Transparency and relations between the WHO Syria office in Damascus and the Syrian Ministry of Health often appear “very gray and not very neutral.” Unfortunately, this has hindered WHO Syria and EMRO from effectively responding to health incidents in Syria, for example the famine in Madaya, continuous pilfering of aid convoys by Syrian armed forces, and an absence of publicly condemning Syrian forces and their allies for attacks on medical facilities of which there have been over 600, 266 of which have been recorded by WHO's own surveillance system since it started operating in 2018. Despite this, the World Food Program office in Syria, in a now-deleted tweet, recently praised Russia on Russia Day for supporting them in delivering “warm and healthy meals” in Syria.

The deconfliction process for protection of health facilities in Syria exposed a possible leak of sensitive information. As part of the process, geolocation data was shared with states involved in the conflict in Syria in an attempt to ensure that health facilities avoided being hit by airstrikes. However, many hospitals continued to be bombed by Russian and Syrian forces. This confirmed the hesitancy and mistrust that some Syrian NGOs had of the system, fearing their information was being used to target them. NGOs reported an increase in attacks on health facilities by the Syrian forces and their allies after being highlighted in media reports. This was the case with Al-Atareb hospital in western Aleppo province, which was struck in March 2021 by an airstrike shortly after a BBC documentary was aired highlighting the work this hospital had done in response to a strike on a nearby school in 2013. More recently, the delay by the UN and donors in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in opposition areas and the potential closure of the border crossing to facilitate life-saving aid to over a million internally displaced people adds more evidence that the current humanitarian and diplomatic approach needs to change.

UN agencies, those who lead them and those who invest in them must renew their moral obligation to set standards of accountability, transparency and norms that are at the very least coterminous with some sense of justice and politically ethical due process. If the UN is to maintain its credibility, then its member states must form a coherent and forceful stance against repressive and corrupt regimes who sit alongside them in Geneva and New York. Electing and turning a blind eye to pariah states should not become the norm. Voting in the UN Security Council to keep the only humanitarian border crossing open in Syria, removing Syria from the WHO executive committee and properly supporting the UNDP and Lebanese civil society’s anti-corruption programs, for example, would be a start in the renewal process. Above all, they must demonstrate and enforce through economic and diplomatic coercion and soft power that “bad actors” can no longer get away with killing civilians and decimating economies and health systems for their own personal benefit and political survival.

Dr. Adam P. Coutts, Senior Research Fellow, Magdalene College, University of Cambridge

Professor Richard Sullivan, Co-chair, The Conflict & Health Research group (CHRG), King’s College, London

Dr. Abdulkarim Ekzayez, Lead Researcher, Research for Health System Strengthening in northern Syria (R4HSSS), King’s College London

Hamish de Bretton Gordon, OBE, Visiting Fellow, Magdalene College, University of Cambridge

Dr. Saleyha Ahsan, Medical Doctor, Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge

Dr. Andres Barkil-Oteo, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC

Dr. Gustavo Fernandez, Director of Bridge Aid Tech and former Medecins Sans Frontieres Humanitarian representative in Geneva