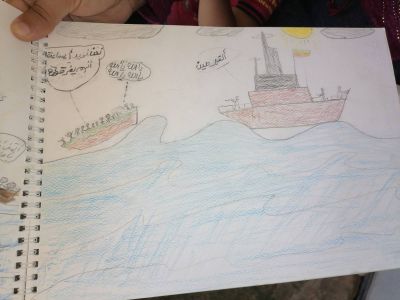

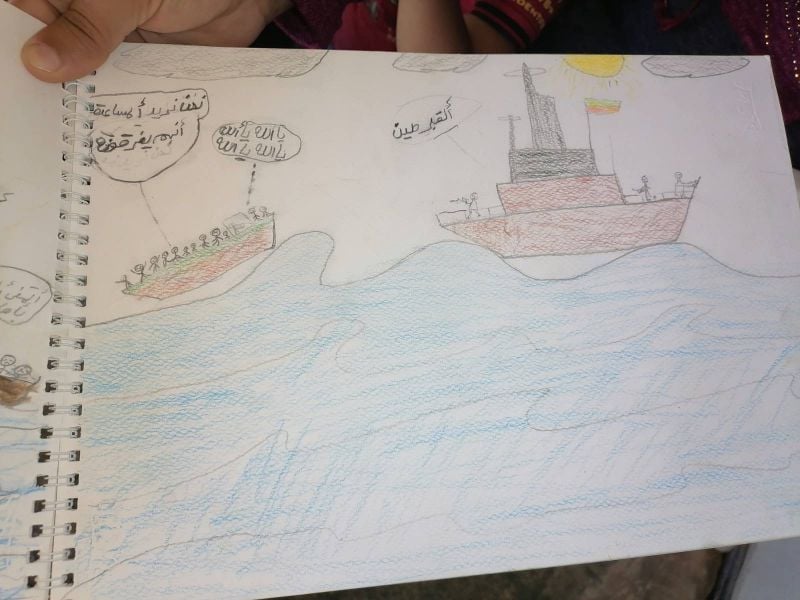

A child’s depiction of their family’s attempt to flee Lebanon by sea. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L’Orient Today)

WADI KHALED, Akkar — Eight years after fleeing from Hama to Lebanon, Youssef was desperate to leave by any route possible, even if that route took him back under the bombing he had fled.

His wife has a chronic heart condition that requires her to take medication they could no longer afford. In 2016, the family was cut off from the monthly aid they used to receive from the United Nations, and now Youssef was out of work too. Their situation was not an anomaly; amid a spiraling economic crisis that began in late 2019, nearly 90 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are living in extreme poverty.

Wanted by the authorities in Syria, returning home was not an option. So Youssef made the decision that an increasing number of refugees in Lebanon have made over the past year. He sold his belongings to pay smugglers $2,500 to take him across the sea to Cyprus, in hopes of bringing his family after him.

“The last period, I didn’t have any work. I didn’t have anything,” he said. “I sold everything to be able to pay for myself, my telephone and various other things. My wife’s gold, we sold it.”

But after taking his $500 deposit, the would-be smugglers disappeared.

“I spent about a month going back and forth with them,” Youssef, who asked that his name be changed for the security of his family, said. “Finally they blocked me [on the phone and WhatsApp], and I didn’t learn anything more about them.”

That was in November. In March, Youssef decided to try another, even riskier route out of Lebanon. He left his wife and son with his wife’s parents and paid another smuggler $1,000 to take him from the Lebanese border to rebel-held Idlib, risking arrest by Syrian authorities if he were to be caught on the way. From Idlib, he hoped to cross into Turkey and then continue on to Greece, but he spent two months waiting on the Turkish/Syrian border before he managed to cross.

“The situation in Idlib is really miserable . You don’t know when you might die,” Youssef told L’Orient Today via WhatsApp as he waited to cross the border. “At one time there is bombing, at another time explosions, kidnappings. Al Nusra” — the Islamist militant group currently known as Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham — "kidnaps people. There are robberies … For the past two months, every day I think I’m going to die.”

The view toward the Syrian border from Wadi Khaled in north Lebanon. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

The view toward the Syrian border from Wadi Khaled in north Lebanon. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

Amid crackdowns, more desperate journeys

While the spiraling crisis in Lebanon has pushed an increasing number of people — the vast majority of them Syrian refugees — to attempt the sea journey to Cyprus this year, the difficulty of crossing the Mediterranean may be pushing others, like Youssef, to potentially more dangerous routes.

In the first six months of 2021, the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, recorded 13 attempted boat crossings from Lebanon to Cyprus — a total of 659 people, five of whom were Lebanese and the rest Syrian.

The number represents a significant increase from precrisis times. In 2018, 490 people were recorded as attempting the crossing; in 2019, the number was 270.

The increased flow of migrants and asylum seekers coming not only from Lebanon but also directly from Syria led Cyprus to declare a “state of emergency” in May and appeal for help from the European Union. Cypriot authorities have called on the Lebanese government to step up its border enforcement to stop boats from crossing. Last month, Cypriot Interior Minister Nicos Nouris met with the head of Lebanese General Security, Abbas Ibrahim, to discuss “the issue of illegal immigration to Cyprus and how to deal with this phenomenon in the best and most effective way possible.”

Only four of the boats that left Lebanon this year actually reached Cyprus, Lisa Abou Khaled, a UNHCR spokeswoman, said. The others were stopped by Lebanese authorities before getting to international waters, turned back by Cypriot authorities on arrival or drifted up to Syria, where they were reportedly stopped by local authorities.

Last month, in a case that drew outcry from rights groups, Lebanese General Security deported to Syria at least five Syrian refugees who had been on a smuggler boat that was pushed back to Lebanon by Cypriot authorities. Officials cited a controversial Lebanese government decision from 2019 authorizing them to forcibly deport Syrians who had entered the country illegally after April 24 of that year.

The other Syrians on the vessel, who had entered Lebanon before 2019, were held in detention for several days and then released.

One of them, Nour, a woman from the Aleppan countryside who had attempted the journey with her three children, told L’Orient Today that until recently, she had resisted the idea of going by sea.

Her husband had made his way to Cyprus five years ago, planning to apply for family reunification once he established himself there, she said. But upon his arrival, they learned that he was not eligible to bring his wife and children.

“A lot of people told me to go by sea, and I said, ‘I don’t want to risk my children’s lives.’ I completely refused the idea,” Nour, who also asked that her real name not be published, told L’Orient Today. But then came the collapse of the Lebanese currency, skyrocketing inflation, and increased security concerns, particularly in the wake of the August 2020 Beirut port explosion.

“When I saw the situation here had become unbearable, and my husband couldn’t come here, and I saw people were going [by sea] and arriving, I decided to risk it," she said. "It turned out to be the worst adventure in my life.”

She sold her tent in the Bekaa Valley and all her household belongings to get the money for the trip — $2,500. She handed $300 to the smugglers before embarking; the rest was to be paid on arrival.

A Lebanese Army naval patrol sighted and pursued the boat as it was leaving Lebanon, Nour said, but was not able to catch up with it before it reached international waters.

Within sight of the Cyprus shore, the refugees were stopped by a coast guard boat and left sitting in the water for 13 hours before being loaded onto another vessel and sent back to Lebanon. The passengers had told the coast guard that they were coming directly from Syria, because the Cypriot policy is to turn back boats coming from Lebanon but not from Syria.

However, the Lebanese Army had informed the Cypriot authorities that the boat was coming and sent pictures of the vessel.

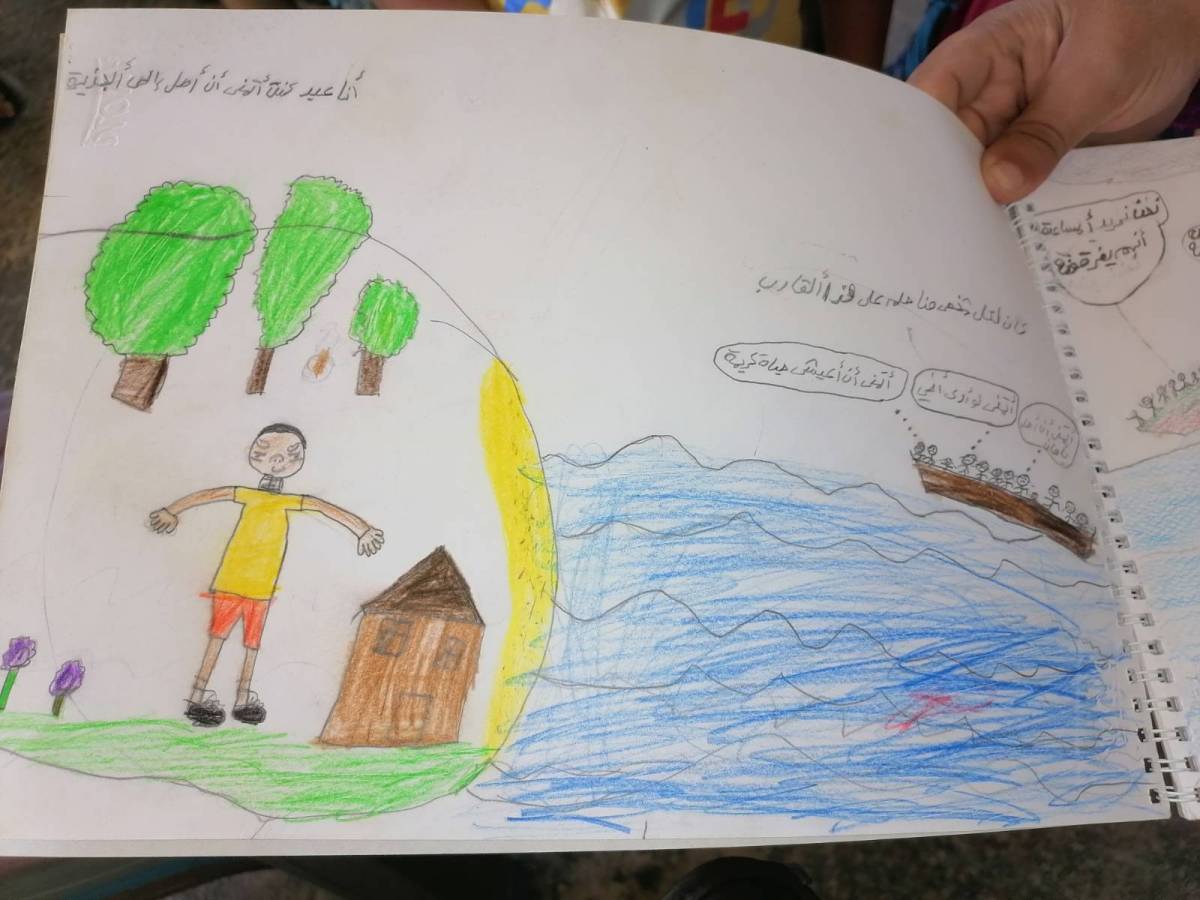

A child's image of the life that awaits at the end of a dangerous crossing. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

A child's image of the life that awaits at the end of a dangerous crossing. (Credit: Abby Sewell/L'Orient Today)

Representatives of the Cypriot Foreign and Interior ministries did not respond to requests for comment on the increased anti-smuggling enforcement efforts. A Lebanese Army spokesperson said only that navy patrols have stopped 21 would-be smuggling boats and arrested almost 525 people this year. (The numbers differ from those provided by UNHCR because UNHCR tracks only the vessels that are reported to it.)

Although the odds of reaching Cyprus look increasingly unfavorable, several refugees who had unsuccessfully attempted the journey told L’Orient Today that they would try again.

“If the UN doesn’t help us to travel, we will try again once, twice, three times until in the end either we die in the sea or we arrive, because we can no longer bear to live like this,” one woman said.

Where one route closes, another opens

“History has demonstrated that refugees — and the human smugglers who help them to cross closed international borders — are remarkably adaptive and innovative, and will find new routes to places of safety, whatever obstacles are placed in their way,” Jeff Crisp, an expert on refugee issues and research fellow at Oxford University’s Refugee Studies Center, told L’Orient Today.

In light of this, Crisp said, it would not be surprising if Syrian refugees in Lebanon who were previously considering the trip to Cyprus are now mulling other, more dangerous routes, such as the overland trek via Idlib and a route by air to Libya and then by sea to Europe, which Youssef said some are now doing.

A smuggler in Wadi Khaled, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told L’Orient Today that he takes people back and forth on the route from the Lebanese border to Homs while others continue on from there to Idlib. On the Syrian side, checkpoints are no problem, he said: “You pay money, and you go through.”

From behind the wheel of a white BMW with tinted windows, the young man pointed to a hill only a few hundred meters away, at the top of which is the border with Syria. A few people could be seen making their way up on foot.

He pointed to others passing by on motorcycles laden with travel bags on their way to and from the border.

“She just came in,” he said, indicating a woman on the back of one of the bikes. “She came from Damascus. From Damascus to Homs it’s two and a half hours, and from Homs to the Lebanese border one hour.”

Not all who cross are fleeing to or from Lebanon for good. Some cross back and forth regularly, preferring to pay a smuggler the $70 fee to Homs rather than putting down $100 at the border and paying for a COVID-19 PCR test as is currently required if they enter legally, the smuggler said.

“Four hundred go, 400 come. Three hundred go, 200 come,” he said. “I can’t keep track.”

UNHCR’s Abou Khaled said the agency has heard only anecdotal information about refugees taking the land route from Lebanon to Turkey via Idlib.

However, an official with the Turkish-backed Syrian Interim Government in Idlib told L’Orient Today that the numbers have risen of people coming both from government-held areas of Syria and from Lebanon over the past year.

“How do they come from Lebanon or from regime areas? They are paying money to people from the regime, and they bring them to the border areas or near to the liberated area, and after they leave them, they enter themselves,” he said. “We don’t know the exact numbers, because they’re coming in by smuggling, so the numbers are not accurate, but every day dozens of people are coming into the north, and afterward most of them try to continue on to Turkey.”

From there, he added, “most of them are going by sea to Cyprus or elsewhere, and there are some who stay in Turkey and find a way to live in Turkey, but most of them are traveling on to Europe.”

The route is risky. The smuggler in Wadi Khaled acknowledged that many travelers get robbed along the way.

Others have been turned over to Syrian authorities by their smugglers, refugees said, and ended up in prison. On the Turkish border, some have been shot by border guards while attempting to cross.

Youssef, for his part, eventually made it across, but the route, he told L’Orient Today via WhatsApp, was “like death.”

“I went three days without food or water and walked more than 30 kilometers,” he said, adding perfunctorily, “Thanks to God of all creation.”

Asked whether he planned to continue on to Europe, he responded, “Now I don’t have money to continue,” followed by a shrugging emoji.

Meanwhile, back in Lebanon, Nour was trying to decide what to do after her ill-fated attempt to cross the Mediterranean. Having left her home and sold all her belongings to pay for the journey, she and her children are now staying in her sister and brother-in-law’s already crowded tent.

She had planned to try again, but she said, “There are not a lot [of boats] going like before, because they are returning people, so the number of trips are decreasing. I really don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Meanwhile, she is stuck in Lebanon, a country that she doesn’t want to live in, and that doesn’t want her but won’t let her leave.

“They tell us here, ‘The Syrians ruined everything. The Syrians destroyed the country,’” she said. “And now we’re trying to escape, and you sent us back.”