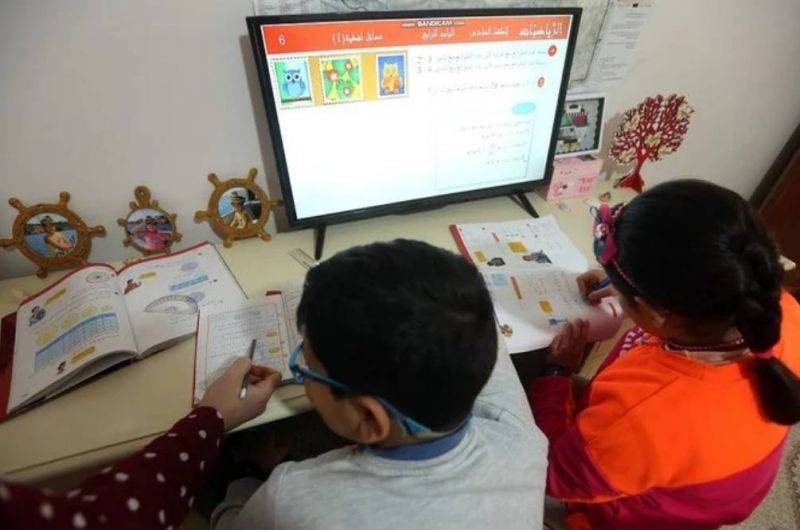

Remote learning is not universally available to children, as schools themselves also do not always have the infrastructure, resources or training to provide effective online curricula. (Credit: AFP)

BEIRUT — Schools are slated to gradually begin reopening their doors this coming Monday, but with caretaker Education Minister Tarek Majzoub’s conditions for a return to classroom learning still unmet, it appears the uncertainty and disruption that have defined the last two years of education in Lebanon will persist.

Save The Children estimates that more than 1 million children across Lebanon have missed out on proper schooling for more than a year due to school closures and the deepening economic crisis, Nana Ndeda, policy advocacy and communications director, told L’Orient Today.

Disruption began in late 2019 when the outbreak of countrywide protests led the Education Ministry to call for a shutdown of schools that lasted weeks. Then, schools closed their doors once again at the end of February 2020, ahead of the first nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, and many students have not returned since.

“It’s not just COVID-19 we’re dealing with in Lebanon, it’s a whole series of crises,” said Hoda Baytiyeh, an associate professor at the American University of Beirut who specialises in online learning. “All of them are having an impact on children’s education.”

Left behind

While schools have attempted to meet children’s learning needs via online sessions, increasing poverty, financial constraints and a lack of reliable access to internet and electricity means that many children are being left behind.

“We had a parent ask us ‘how can I buy internet for my children while they are hungry’,” said Alaa Hmaid, Save the Children’s education capacity building and development coordinator. “People are prioritizing things other than education.”

Remote learning is not universally available to children, as schools themselves also do not always have the infrastructure, resources or training to provide effective online curricula.

Jo Kelcey, an education researcher at the Lebanese American University, said that many children simply receive texts or pre-recorded videos via Whatsapp, which encourages a pattern of rote learning, rather than real engagement with the material.

“Kids are not understanding classes,” she said, adding that parents often do not have the time or capacity to assist their children with studies.

Myriam (whose name has been changed in line with child protection policy) is a sixth-grade student in Beirut. She said she is struggling to learn as she has to follow lessons on a cell phone that she shares with her sister.

“I am getting lost and I don’t always understand,” she said. “Corona separated me from my school, my friends and my life outside [the home].”

Lydia Abdul Hadi, a teacher in Beirut, said that the switch to remote learning had had a “huge impact” on children’s education, particularly due to worsening internet connectivity and increased power cuts in recent months.

“That’s not to mention the emotional pressure on families and students with the difficult living conditions,” she added.

Reduced access to the teaching and pastoral support provided by schools, or dropping out of formal education altogether, also puts children at higher risk of abuse, Hmaid said, including domestic violence, child labor and early marriage.

Going backwards

Even those children with parents who are still able to provide the necessary materials for online school, are struggling with being away from the classroom.

Neither of Renee El Khoury’s sons have attended their school in Metn in person since February last year, instead they follow lessons on laptops at home. But they are missing the interaction of in-person class.

“I’d really like to be able to go back to school and see my friends and learn more,” said 10-year-old Petersam.

His mother has noticed a slowdown in the progress her children are making in class, as lesson time has been cut down to just four hours per day.

“It will take time to catch up,” Khoury said. “What they are getting right now is not enough.”

Feras Kheirallah said both his sons’ learning had “gone backwards” in the last year, during which they have only been at school for a total of around two weeks.

His youngest, 4-year-old Eliah, did not engage with online lessons at all, so Kheirallah and his wife decided to let him spend his days playing with similar-aged children instead.

His 10-year-old, Noah, has struggled with the isolation and boredom of home schooling and has “withdrawn into himself.”

With children unable to interact with their peers and teachers on an everyday basis, Baytiyeh warned of long-term effects on children’s emotional and mental growth.

“I really worry about children’s well-being,” she said. “Development is not just about learning.”

Not a priority

In the last year, 6-year-old Adreana has only been to school for around a month, her mother, Pascale Khoury, said.

“She finds it really difficult to focus,” Khoury said. “When school stopped, she kept asking ‘why’ — she didn’t understand.”

“It’s unfortunate for kids their age, they’re not living their childhood properly.”

Khoury said the ongoing closure of schools was particularly frustrating given that bars, restaurants and other leisure venues have been allowed to welcome customers at various points throughout the year, partly under pressure from powerful union lobbies.

“It’s a typical decision of our corrupt government,” she said. “They denied the children their basic right to be taught properly.”

Earlier this month, caretaker Education Minister Tarek Majzoub hit out at his government and Parliament for what he described as a failure to properly fund the education sector, ensure internet access and provide PCR tests and COVID-19 vaccines for teachers. He called for a weeklong strike from online classes last week, which caused further disruption to teaching.

Public school teachers, particularly those on hourly contracts, have staged multiple protests in recent months over unpaid salaries.

Both Save The Children and Kelcey, the researcher, have heard increasing reports of staff working elsewhere alongside their teaching roles to supplement their salaries, which have plummeted in value with the depreciation of the Lebanese pound.

“It’s worrying that teachers might seek alternative sources of income,” Ndeda said. “There is no guarantee that teachers will be there for children when they go back to school.”

On Wednesday, secondary school teachers announced that they would suspend online lessons for the rest of the week in protest at the challenges brought by remote teaching and against a return to schools before teachers are vaccinated against the coronavirus.

Majzoub had called for schools to begin reopening their doors on Monday in a gradual return to in-person teaching, starting with students in exam years. However, this was conditional on staff being assured COVID-19 vaccinations and schools being provided with rapid coronavirus tests.

A source at the Education Ministry said that the minister is waiting for a response from the Health Ministry on these requests and that it is still not clear what will happen on Monday.

“The longer children are out of school,” Ndeda said, “the more difficult it becomes to reverse the losses that have been made.”